Foreward:

I’ve been writing fewer and shorter pieces lately. That’s fine. My interest in writing has waned as other hobbies (mostly rollerblading) have sucked up my time. I’m committed to this one-shot workflow for writing, and I’d rather publish smaller pieces on schedule than get stuck in rough draft hell. But I do have ambitions of writing substantive and durable articles; something that I’d be proud to share with colleagues, rather than ephemeral twitter-thread-like content. I’ve been kicking around the idea of a “cosmetics monetization handbook”, and my previous article inspired me to write more on the topic. So I’m going to lay out an outline for the whole project, and try to write a chunk every week. It’ll look something like this:

Cosmetics Monetization Handbook

What are cosmetics?

What player motivation do cosmetics serve? [Done, sorta. Needs revisions]

What games are viable for cosmetic monetization? [This]

What attributes of cosmetics drive demand?

How do you design game systems to support cosmetics?

How do you produce cosmetic content efficiently?

Today’s article tackles point (3)

What games are viable for cosmetic monetization?

As we’ve established, cosmetics principally serve player desires for social prestige and self-expression. Games that are already focused on those player needs or have core systems to promote them are well-positioned to monetize with cosmetics. Social surface area is provided by rich social interactions and visible player avatars. Social status emerges from in-game social hierarchies or real-world connections. Ideal games possess both the surface area to send signals, and social status associated with those signals.

Social Surface Area

Fashion is social signalling, and that requires a society to signal to. This requires meaningful player-to-player interaction in the core game loop. Simply having clans in a solitaire game like Candy Crush won’t cut it. MMOs and team esports are particularly strong here. MMOs’ shared worlds with player avatars creates a huge amount of incidental interaction. Even if you’re playing solo and minding your own business, you’ll inevitably encounter other players and make snap judgements based on their appearance. Are they weak or strong? Are they friendly or hostile? Would their class compliment yours? As you observe other players, you’ll naturally take note of their cosmetics.

Active interaction in gameplay further amplifies this focus on others. Team esports and cooperative games excel here. You have to pay close attention to teammates to coordinate tactics, and they can really stand out during a big play or narrow escape. In late-game MMOs, you are forced to team up to tackle difficult dungeons and raids, or join clans to unlock new progression pathways. This further forces you to observe and evaluate others based on first impressions, as well as form persistent social bonds.

Solo competitive games suffer here. One-on-one games limit the number of observable players to one per game, compared to nine in a 5v5 game like LoL or Counter-Strike. Even if plenty of other players are present like in Tetris 99, if your gameplay is mostly focused on your own actions rather than your opponents’, then you won’t pay attention to their cosmetics.

Avatar

Identity is key to both social signalling and self-expression. You need a way to channel your ego into tangible form, and avatars were designed for that purpose. Avatars are your on-screen representation, be it an animated 3D character or a static icon. Avatars are best when they are an individual humanoid for you to project onto. Map skins in Dota are the polar opposite; the cosmetic is applied to the impartial game world rather than your player character, so it fails to provide any self-expression. Real-time strategy games also suffer here, since it is hard to psychologically connect with dozens of tiny troops from a bird’s-eye view. Stronger player-to-avatar connections create tighter ego extensions, and enhance the quality of the social surface area.

Persistence also helps egos connect with avatars. Most games are designed around some player-character persistence. MMOs perhaps are the clearest example; you may invest hundreds of hours into a particular character and see it as an extension of yourself. Character-driven games like hero shooters or fighting games allow players to switch at will, but most players will “main” a particular character in order to become proficient with that particular toolkit and playstyle. This main character naturally becomes a psychological focus and ego extension. Impersistence as a problem has arisen recently with the rise of roguelikes and drafting autobattlers. In these games, your character may be randomly chosen. Instead of having a “main”, you are forced to play a probabilistic blend of branching strategies. Success comes from avoiding irrational emotional attachments to particular characters. In these cases, gameplay is actively working against cosmetic monetization.

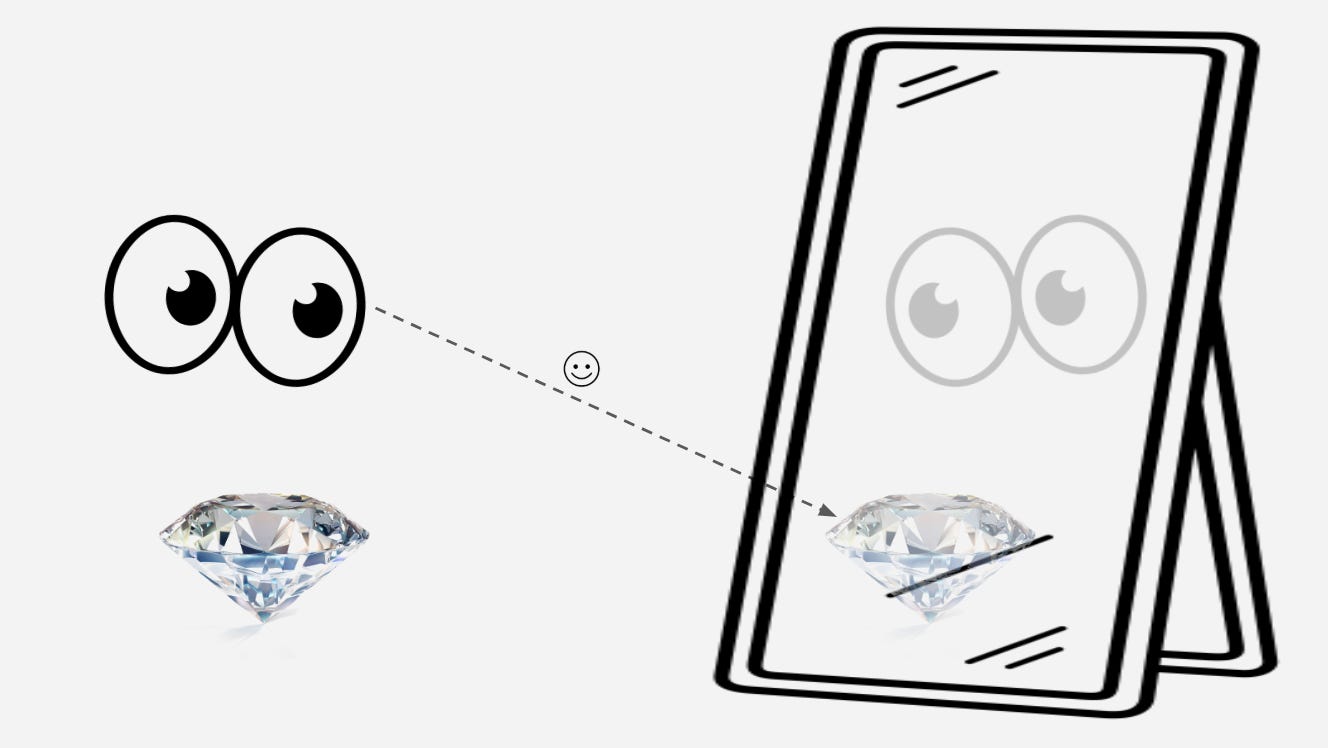

Mirrors

Players ought to be aware of their own appearance; otherwise, they may not realize the impression they are making on others. “Mirrors” in the game promote self-awareness. Third-person shooters, for example, naturally frame your character on the screen, making you fully aware of how you appear to others. First-person shooters struggle here, since you can only see your hands and a gun. Perhaps this explains why Counter-Strike primarily monetizes through gun skins rather than character skins. Though limited, first-person animations can also help emphasize your cosmetics. Counter-Strike has an “inspect” command where your character will show off and fiddle with your weapon. Similarly, card games like Marvel Snap allow players to zoom in on individual cards for full HD glory; otherwise, cards are small icons on a busy game board.

Counter strike 2 | Butterfly knife Fade Inspect and Animation (Updated 28.3.2023)

Stages

Cosmetics need to be visible to others; again, social surface area. “Stages” provide platforms for players to flaunt. Roblox literally has a fashion show minigame. Avatar cosmetics accomplish this naturally in games with rich social interactions. If you can’t see the other players, you can’t see their cosmetics. Fog of war shrouds the stage in real-time strategy games and hampers cosmetics’ appeal. Games can also fabricate stages to promote cosmetics. Overwatch’s victory screen and “play of the game” highlight the winning players, as well as their cosmetics.

Ward skins in LoL are a particularly weak example, as they fail all of the above criteria. Vision wards are temporary, immobile sticks in the ground that are invisible to the enemy team. Wards are un-interactive, un-empathetic avatars, usually off-screen or invisible, and rarely the center of attention. It’s no wonder that nobody buys them.

Physical vs digital card games offer an interesting contrast here. Cosmetics in the form of unique card art or custom playmats exist in both, but garner much more attention in meatspace. You might glance at the neighboring table while waiting for your turn, and spectators may wander by and compliment your foil full-art Japanese-text Jace with matching playmat. In contrast, there aren’t any passerbys spectating your late-night Hearthstone game.

Physical card game players also have a name and a face, and you’ll likely interact again at the same card shop or weekend event. This leads us to the next point…

Status Signals

Social signalling only matters if you care about your reputation with the recipient. These ties are strongest in-person: you’ll see your playmates tomorrow at school or next Friday at the weekly meetup. Recurrent social interaction means that the impression you make today may pay dividends later. Personally, two of my Smash Bros buddies from college became my best man at my wedding and my current boss at work. These in-person relationships will naturally occur for in-person games, like physical card games or offline fighting games. But those are edge cases in our modern world of online games.

If a game is popular enough, you may have real-life friends who also play. Thus, extremely popular games are more likely to have in-person social ties. School is perhaps the highest degree of social interaction in our upbringing, and thus is a particularly compelling social environment. Consider Roblox among grade schoolers, Fortnite in colleges, LoL ten years ago, or WoW twenty years ago. All of those games had social ubiquity among a particular demographic, and all of them successfully monetized with cosmetics. As a corollary, niche indie games inevitably struggle to find the in-person social ties to leverage with cosmetics.

Aptitude or enthusiasm for the game must also be socially valuable. This works best among enthusiast communities, like competitive esports or hardcore MMOs. In some casual games, it is bad to care too much. For example, bringing a custom art snowboard to a weekend ski trip raises your social clout, since you’re surrounded by others who care about snowsports. But bringing custom art cups to play beer pong at a frat party is cringeworthy.

Games with built-in hierarchies naturally create tiers of social status. Players who top the leaderboard, achieve master rank, or are officers in their guild are framed as higher-status within the game community. These players are more likely to own cosmetics; their desire for self-expression converts their emotional investment into financial investment. In some games, they may not even need to spend money. Overwatch gave free cosmetic loot simply for playing; purchasing only granted more of what was already accessible via playtime. This way, owning a rare cosmetic blended signals of “I’ve spent money” and “I’ve played a lot”, sidestepping social stigmas. In other contexts, association with wealth is desirable. Generally speaking, wealthier people have higher social status in meatspace. There’s plenty of pearl-clutching articles about schoolkids bullied for being too poor to buy Fortnite skins.

Regardless of how high-status players obtain their cosmetics, ordinary players see the correlation and make subconscious associations. Their idols bear cosmetic signifiers, and rando baddies don’t. Buying cosmetics puts you one step closer to the cool kids’ club. Monkey see, monkey do.

Adverse Signaling Traps

This can backfire if certain cosmetic signifiers are too directly associated with specific achievements. Many games reward players with cosmetics for reaching high levels or rankings. Sometimes, this achievement level is so special that players stop buying other cosmetics altogether. It’s best to reward these cosmetics at a low enough threshold to create space for upward mobility. LoL, for example, rewards skins for achieving gold rank (roughly top 10%). This is high enough to be desirable, but low enough that the gold-rank skin is no longer prestigious when players reach platinum or diamond rank.

Gameplay-impacting cosmetics also come with strings attached. Among Us, for example, is a social deduction game where “traitors” attempt to deceive other players. Distinctive cosmetics make players stand out and may draw unwanted attention. This is hardly a factor in a casual environment, which is fortunately most of the playerbase. But competitive players do take this into consideration, and it affects their spending. In LoL, Faker (the GOAT) famously avoided champion cosmetics. He wanted champions’ attack animations to be as consistent as possible so that he could play around visual cues, and he avoided animation-altering cosmetics. This created a trickle-down effect where Faker wannabes would mimic his behavior. Fortunately, Faker was an outlier in this regard; most pro players’ desire for self-expression trumped this miniscule gameplay impact.

When designing game systems, be wary of negative associations with the cosmetics you are trying to sell.

Not all games can monetize cosmetics. The ideal game has a large social surface area: interactivity, humanoid avatars, mirrors and stages. The ideal game also has social status associated with cosmetics, created through in-person relationships or correlations with hierarchy. Within this framework, popular MMOs, team esports, and ubiquitous social games are best-equipped to monetize cosmetics. Empirically, this certainly seems to be the case.

This article focused on game genres that best support cosmetics. Next time, we’ll discuss the cosmetics themselves, and what attributes drive demand.

This is the type of knowledge that's extremely hard to find - successful companies (and there are very few doing it well with cosmetics) keep knowledgeable folks happy and within the company. And well, learning from not-so-successful ones can't be complete.

So, thanks for sharing!