(This is a draft script for a talk I’m giving at GDC on March 20. Come by if you’re around!)

Summary Blurb:

Video games and economics can learn a lot from each other. “Forever games” are particularly fertile ground for economics research, thanks to their multiplayer dynamics, bevy of incentives, and large stable playerbases. Join our talk to hear about video game analogues to real-world phenomena like gray markets, crime statistics, and dating apps.

Intro:

Hi, Welcome! I’m Eric and I’m here to talk about the intersection of video game design and economics. First we’ll examine some analogues between economics phenomena and video games. Then we’ll discuss why video games are particularly good for economics research. For game developers out there, I encourage you to search for analytical frameworks and design solutions in the broader space of social science.

Economic Phenomena in Video Games

Perverse incentives – The Cobra Effect

The story goes like this: back in the British Raj in India, cobras were biting people and killing them. The government wanted to reduce the cobra population, so policymakers introduced a cobra bounty – they’ll pay money for cobra skins. To optimize their dead cobra production, savvy entrepreneurs started cobra farms, breeding cobras and harvesting their skins. The policymaker’s incentive was perverted to create the opposite effect!

World of Warcraft has regions of the world map that are “contested”, where hostile Alliance and Horde players might run into each other. In order to encourage player-vs-player combat between factions, WoW introduced an “Honor” system whereby players would accumulate points from killing enemy players and receive rewards accordingly. However, killing enemy combatants in spontaneous combat is difficult. Instead, players found it expedient to organize “point-trading”: groups of Alliance and Horde players would meet at a designated location and take turns killing each other to accumulate points. A system designed to drive spontaneous conflict actually promoted coordination.

Gray Markets – Flavored Vapes and Smurf Accounts

After decades of downturn, nicotine consumption has seen a huge resurgence accompanied by fruit flavored vapes. Moral panic ensued, and California legislators banned flavored nicotine products to prevent the corruption of our youth. However, flavored vapes are still easily obtainable; almost any local smoke shop will have shelves full of fruit-flavored vapes. There is practically no enforcement of the ban, and the first offence is a very small fine. These smoke shops are willing to continue selling flavored vapes despite the ban. One explanation for this disconnect is that the government doesn’t actually want to enforce the ban. Enforcement is expensive, and actually shutting down these smoke shops would reduce tax revenue and upset businessowners. Legislators want to take the moral high ground and appear to represent public health interests, but don’t actually want to follow through on enforcement.

League of Legends’ terms of service forbids selling accounts; each account must only be played on by one human. Account-selling is seen as an abuse of the game. Players who buy accounts are usually banned for cheating or saying too many racial slurs, and buying high-level accounts allows them to totally circumvent the ban. Moreover, the account sellers are creating high-level accounts by running bot scripts to mindlessly play games and level up; these mindless bots degrade the game for the human players they are matched with. Riot Games wants to take the moral high ground here and forbid account selling. However, this practice of selling accounts to rapidly circumvent bans is actually financially beneficial for Riot. Banned players on new accounts will often spend money to buy their favorite champions and skins. They are usually high-engagement and high-spend players (as evidenced by their willingness to purchase accounts) who likely also have social connections in the game. Thus, Riot turns a blind eye to these account-selling operations.

Veblen Goods – Lambos and Skins

Thomas Veblen was an economist who criticized the inequality and capitalism of the gilded age. He pushed the idea of conspicuous consumption, wherein people flaunt their purchases for social clout rather than the intrinsic utility of the goods themselves. In this vein. “Veblen goods” are products that see greater demand when their price is higher. This runs counter to most goods, where higher prices cause fewer purchases. For a Veblen good, the high price itself is part of the social clout the good confers.

Conspicuous consumption is alive and well today in luxury status goods; lambos, rollies, vvs, etc. (Translation: Lamborghinis, Rolex watches, and diamonds). If you’ve ever seen finfluencers selling get rich quick schemes, think of the products they conspicuously display in their videos.

Many esports games monetize primarily on cosmetics. To promote competitive integrity of the esport, pay-for-power is mitigated and most deep end monetization comes from skins with no gameplay impact. Competition is fundamentally social, and the demand for in-game cosmetics depends on their social clout. Empirically, there is a correlation between players’ skill level and their willingness to purchase expensive cosmetics. Many games find that their high-end items sell more units when they are priced higher, since it clearly signals their elite status.

Fair Division – Cake Cutting Problem and Magic the Gathering

The “Cake Cutting Algorithm” is a classic problem in game theory. Suppose you have a cake and you want to divide it fairly among a group of people. But the cake might have a bunch of idiosyncratic properties; there’s chocolate toppings here, fruit and berries over there, and extra frosting around the edges. How do you fairly divide up the cake? Rather than relying on calculations or heuristics, the cake cutting algorithm leaves it up to the people. One person divides the cake up into slices, and everyone else takes turns picking a slice. The cutter gets the last slice. In this way, the cutter is incentivized to cut the cake as evenly as possible; they will get the least desirable slice, so they want to cut the cake to maximize the worst-case scenario. This cake-cutting algorithm can be used in high-stakes real life scenarios, such as estate inheritance.

Magic the Gathering fans will recognize this divvying process from cards like Fact or Fiction. The card text reads:

Reveal the top five cards of your library. An opponent separates those cards into two piles. Put one pile into your hand and the other into your graveyard.

Though the goal is no longer fair division, the decision-making is nuanced and skillful. Cards are more idiosyncratic than cake; the divider needs to evaluate each card’s impact. Moreover, the value of each card depends on the board state as well as the cards each player holds. For example, there might be a powerful combo card in the 5 cards being divided. The divider needs to evaluate whether or not their opponent has the other components to assemble the combo, whether there is some way to disrupt the combo, and factor that into creating two equally valuable piles. The Fact or Fiction player then has to select between the two piles, performing a similar evaluation.

Fact or Fiction was an instant hit when first printed 25 years ago, and has been frequently reprinted ever since. Similar divvying mechanics have been often reused, and the card is cited by Mark Rosewater (MtG’s lead designer) as one of Magic’s most influential cards.

Counterstrike Gun Prices

Counterstrike gun skins are traded on an open market with floating prices. We can observe all the usual price changes caused by supply and demand effects.

Demand Shocks – Nerfs and Buffs

Counter-Terrorist teams in Counterstrike have access to two main rifles – the M4A1-S, and M4A4. Historically, the M4A1-S was the clear favorite, so Counterstrike nerfed its power in September 2015. As a result, players shifted their usage towards the M4A4. Market demand for their respective gun skins shifted as well.

Popular M4A4 skin prices shot up overnight, nearly doubling in price in a hard step function. (ex: Asiimov, $25 → $40)

M4A1-S skins dropped accordingly. (ex: Cyrex, $25 → $17)

Curiously, the Cyrex price drop was not as sharp as the Asiimov, with a gradual decline over the following weeks. This suggests that players are quick to buy new gun skins for active use, but slow to sell off unused inventory.

This type of demand shock is analogous to government policy changes. Whenever the government announces a new tariff or subsidy, stocks in affected industries respond accordingly.

Substitution – New Skins Cannibalize the Old

The iconic AK-47 is canonized in media as the wild weapon wielded by the “bad guys”. Counterstrike is no exception, as the Terrorists’ AK-47 is arguably the best gun in the game. When new gun skins are released, players pay particular attention to new AK-47s.

But attention is a limited resource, and new skins draw demand away from old skins. This substitution effect can be clearly seen on the prices for old skins, who fall out of fashion and drop in desirability. (ex: Aquamarine Revenge, $40 → $30)

In fixed-price marketplaces such as League of Legends, this substitution effect manifests as reduced sales volume on older content. But in floating price marketplaces, we can observe this directly in the market price.

Income Effects — Virtual Stimmy Checks

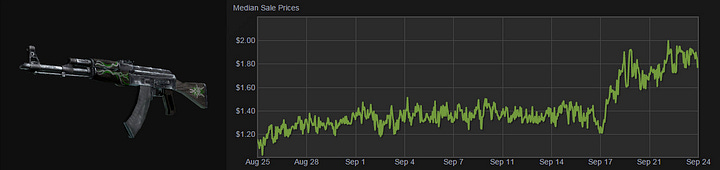

Not all AK-47 skin prices dropped at the same time. Counter-intuitively, low-end skins (ex: Emerald Pinstripe, $1.40 → $1.80) actually increased in price! There is another effect at play here — income from cases drops.

Around the same time, a new loot box dropped. Counterstrike loot boxes are given to players for free, and many opt to sell them on the secondary market. For the first few weeks, new boxes sell for about $1, so these free loot drops functioned similarly to a stimulus check.

With a few dollars in hand, players look for skins to buy within their price range. Cheap guns like Emerald Pinstripe see a surge in purchases. This is a textbook example of income effects pushing up demand.

Games are an Econ Laboratory

Why are there so many parallels between economics and video games? Several reasons.

Multiplayer interaction with emergent behavior

When you have many individuals acting in their own self-interest within a complex system that supports emergent behavior, you will see economic behavior emerge. MMOs are perhaps the game genre that best exemplifies this. Evidently, many examples above were drawn from MMOs.

Game Designers are Omniscient and Omnipotent

Data is plentiful and precise, thanks to computers and telemetry. Moreover, game designers have a great deal of control over the game itself. For example, Rocket League designers can change the inertia or gravity of the ball by tweaking a few numbers, and quickly observe the impact it has on statistics like goals scored or turnover. However, if the NBA wanted to change the weight of a standard basketball, it would need to be approved by various agencies, and then new basketballs would need to be produced and gradually introduced to phase out old basketballs. A logistical nightmare. Measuring the change in 3-point shots afterwards is its own problem, with imperfect observation and long lag times.

Incentives and Adaptation

Games are full of incentives; high scores, level-ups, hit points, and gold. Games are especially good at creating powerful psychological incentives with minimal material inputs; gamers will try much harder to upgrade their weapons than they will to find tax breaks. As a result, games can manipulate incentives in a way that players will respond to and researchers can observe.

Gamers are sometimes more adaptive than their real life counterparts. For example, in American Football, there has been a recent trend away from extra points via field goals and towards the riskier 2-point conversion. This trend in professional play was predated by a similar trend in video game play – top Madden players learned the risk-reward payoff of 2-point conversions may actually have been worth it, and adopted those tactics before real-life offensive coordinators did.

Long-Term Stability and Steady States

Much of economic analysis looks at changes from a steady state. When Trump flip-flops on some crazy tariffs, analysts look at the change in stock prices, not the absolute value. The impact is easier to evaluate when the prior state was steady. Forever games (long-lived live service games), as their name implies, have reached a steady state. Analysts have plenty of prior data to work with, and short-term effects like marketing buzz or new player dropoff distort results less.

Consider those Counterstrike gun price charts from earlier. The effect of the M4 nerfs are immediately apparent thanks to the very steady price prior to the nerf.

A/B Tests are Easy

Randomized Controlled Trials (aka A/B tests) are the gold standard for scientific research. But running experiments can be difficult. Phase 3 clinical trials cost tens of millions of dollars, recruiting undergrads for psych studies introduces huge potential biases, and some fields find it impossible to run experiments, like astronomy and meteorology.

Video games, by contrast, can run large-scale controlled experiments pretty easily. You may not be able to A/B test the weather on Earth, but you can A/B test the weather in World of Warcraft; split the game servers into two groups and change the weather in half of them. The game developer’s omnipotence allows for anything to be changed, and their omniscience allows for any outcomes to be observed.

Stakes are low, which allows for risk-taking

The Corrupted Blood incident was a virtual pandemic in World of Warcraft. A newly introduced boss monster would infect players with a “corrupted blood” ailment that could transmit between players. This was meant to be constrained to the boss fight, but escaped into the broader world due to a bug. Corrupted blood spread through the general population, as players infected each other by proximity. Non-player characters even became asymptomatic carriers, as they were able to spread the infection but did not reveal any symptoms. While many players opted to log off, some continued to role-play in the game, spreading public awareness of the pandemic, encouraging quarantine, and setting up medical stations where healers cured infected players. Real-life epidemiologists took interest in how MMOs, unlike mathematical models, could capture individual human responses to disease outbreaks rather than generating assumptions about behavior.

No real people were harmed in the making of this pandemic. While this incident was an accidental programming error, WoW designers have since intentionally introduced pandemics into the game. That’s all fine and dandy when it’s virtual video game characters dying, but there’s no way you could run this kind of experiment in the real world. The low-stakes environment of video games allows designers to be more aggressive and run wild experiments.

Drawing Inspiration

These parallels run both ways. As game developers, we should be looking to draw inspiration from real-world economics. While we may have better data and design tools, academia has spent decades developing theories that we can draw on rather than reinventing the wheel.

Crime Statistics and Toxicity

League of Legends is legendary for its toxicity. Apparently, competitive games with anonymous teammates create a lot of within-team hostility. Player behavior was a perennial issue, and I was tasked with creating a framework to define, measure, and reduce the harm. The problem was that there wasn’t much common knowledge on the subject, as esports were a relatively new phenomenon.

Crime, however, is as old as society itself. I drew inspiration from real-world crime statistics. The US uses two methods to measure crime; police reports and victim surveys.

Police reports provide detailed front-line data, and are standardized so that local data can roll up into nation-wide aggregates. This data is powerful but suffers from reporting bias; incidents that tend to go unreported such as domestic violence or under-policed neighborhoods will be under-represented.

Victim surveys capture the other side’s perspective. A nation-wide survey asks individuals what crimes they have been victims of. This provides a much richer and more honest perspective on crime, albeit at a lower sample size. By looking at differences between police reports and victim surveys, criminologists are able to identify what crimes go under-reported and what neighborhoods are under-policed.

We mapped this framework onto LoL. Police reports were analogous to in-game detection algorithms. LoL tries to detect harmful behavior by looking for players going AFK, repeatedly dying on purpose, or typing racial slurs. This provides high-volume and consistent data, but it only detects what it is defined to detect; if players find new ways to be toxic that skirts the detection algorithms, they will fly under the radar. Victim surveys were analogous to post-game reports, where players can report toxic behavior by others. We supplemented reports with a new post-game survey about toxic behavior, providing higher-fidelity text feedback and avoiding the opt-in bias of reports. By utilizing best practices in real-world crime statistics, we were able to map a successful framework onto LoL rather than reinvent the wheel.

—

Nintendo’s legendary designer, Shigeru Miyamoto, believes great game ideas draw inspiration from outside video games. Zelda was inspired by exploring the wilderness, Pikmin was inspired by watching ants in his garden, and Star Fox was inspired by the TV show Thunderbirds. Looking inward to existing games will cause designers to retread the same steps, but looking outward can illuminate new paths.

Similarly, I believe that, in our desire to analyze and understand games, we should look outside to real-world economics and social sciences to draw inspiration.